No. I could not farm the whole state. It isn’t going to happen. It would cost something like $176 billion to buy the farmland. Besides, we are better off with a half million small farms than with one giant farm as more farmers can do more work, cast more vision and solve more problems. Break the herds and flocks listed below out to an appropriate number of farmers if you want but keep the big total listed below. That’s realistic. Let’s have some fun with one big herd today though.

We use cattle to cycle nutrients and fix carbon. To build healthy soil. They also heal riparian areas. This is accomplished by timing exposure, measuring mob density and allowing adequate plant recovery. The problem I have is I don’t have a mob. I have 60 hooves, not 60,000,000 hooves. Not yet anyway…

What would happen if we used the whole state of Illinois as a pasture? Pretend I could rent it or buy it. Work with me here.

First, let’s make room for people. We need people. People are good. More people allow us to achieve a more complete utilization of the land and resources because I can’t do it all. I need help harvesting the nuts and berries. I need help making the calculations for the jump to light speed. I need guitarists and poets and artists and carpenters. I need bakers and brewers and electricians and computer programmers. I need inventors and dreamers and deadbeats. Biographers, journalists, morticians, pastors, truckers, used car salesmen and bankers. I need overweight doctors, professors without truth and people with Facebook accounts who think they have all the answers. I need people who can manage resources efficiently and people who will gamble it all away in one roll of the dice. I need people cheering for the red team and people cheering for the blue team and people who think they are above the game. I need opportunities to serve in a community and a community to help me when I’m in trouble. So let’s leave room for the people. The cows are a tool. The dirt is the place. The people are the purpose.

Illinois has a population of 12 million. 8 million of those live in or around Chicago. People are often shocked to learn you can drive 5 hours out of Chicago and still be in Illinois. In fact, There are 37 million acres in Illinois. So let’s give everybody an acre. They don’t have to live on that acre, but we’ll reserve that land for retail, roads, recreation, housing, gardening…whatever. Everybody gets an acre. In fact, let’s reserve another 3 million acres for the unborn. Normally we, as a nation, allocate equal space for lawn and for recreational horse pasture. I may not be leaving that much cushion. You may have to buy your horse hay from Missouri.

That leaves us with 22 million acres. Awesome possum. Cool beans. We currently farm 26 million acres in Illinois so we are ahead of the game already.

In Illinois we basically need a little less than two acres per cow and her follower. That would mean we need to come up with 11 million cows (and 110,000 bulls!). But there are only a million cows in the state currently. Heck, Texas doesn’t even have 11 million cows. But we have the appropriate soil and sufficient rainfall and we would harvest something like 10 million calves each year. Basically one beef for every non-vegetarian resident. The USDA says we ate 195 pounds of meat per person in 2000 so you probably won’t be able to/shouldn’t eat the whole beef. We’ll have to sell a portion of our production outside of the state.

And 11 million is just the starting point. We have some of the best soil in the world. Right here. If we can grow 400 bu/acre corn we can surely build grasslands to support one cow per acre…or maybe just one per 1.5 acres. But let’s stick with one cow per two acres and add in sheep instead.

We can comfortably run 4 ewes per cow…so 44 million ewes. So 88 million lambs each year. 88 million. Not only do I need to gobble up a whole beef each year , I need to eat 7 lambs each year. That’s too much meat. Lamb may become the new chicken. The cheap meat. We’ll have to export some of it to Indiana and Missouri…or other states if our neighbors catch on and appropriately stock their land.

But we aren’t finished. Imagine the mess behind the herd. We need a big-ole flock of layers to follow behind them and clean up the mess. We currently run 10 layers per cow and I think that ratio is about right. So we need to run something like 110,000,000 layers free-ranging behind the cattle. The flock may force us to rotate some grazing land into grain production seasonally but that really shouldn’t hurt our grazing total. We’ll also need some help hatching those eggs, let alone collecting and packing and selling 6 million dozen eggs every day. BTW, that’s half of the current egg production of our entire nation so maybe we should cut back our egg production…if for no other reason to lessen our grain needs. We will be grazing around 400 square miles each day with our herds and flocks so the more we distribute the materials handling the better. We should have egg-packing and distribution facilities all over the place. We could probably butcher the flocks and make canned soup and canned cat food and…whatever else while we are in Chicago each fall and they can compost the remains for sale to the millions of Chicago gardeners. We’ll pick up the new flock of 110,000,000 pullets when we pass University of Illinois. Maybe the pullet logistics could become an ongoing research program.

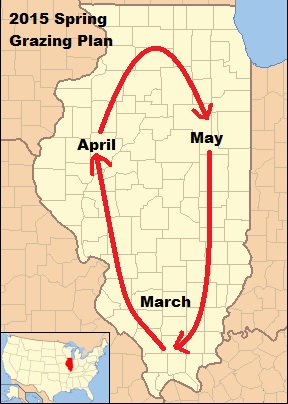

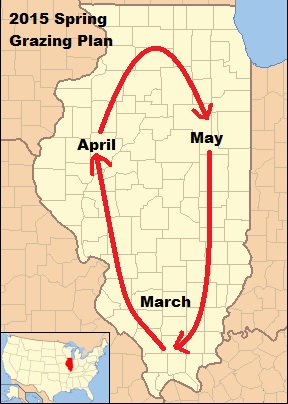

The flocks and herds will pass by quickly going from Jerseyville to Jacksonville in two days. One day the grass is waist-high, the next there is a carpet of grass and manure. Like sweat after a workout it only lasts a little bit then the recovery continues until the next workout. Every three to five months the herd will pass between Effingham and Olney then on past Harrisburg so we can wave at Metropolis then up again between Pinkneyville and Chester, across the flat stretching from St. Louis to Peoria to Rockford, skirting the freightened masses of Chicago who have never seen cattle before as we wind down to Champaign and back around again. Every three to five months we’ll graze, trample and manure the entire state, building inch after inch of soil on a dense fabric of roots and trampled grass blades…a blanket that cushions and protects the soil from ice, wind, sun and rain. Schools will let the children out for the day to see The Jordan herd pass by…a sight their grandparents never imagined. Letters will be written to editors complaining about the flocks of wild birds that accompany the herd migration and late pizza delivery caused by cattle crossing the road for hours. Chickens will follow behind…all 110 million of them, scratching out bugs and leaving additional manure. (How would that even be possible? Thousands of school buses converted to chicken houses driving from place to place? Maybe train cars full of chickens? Train cars full of chicken feed? Honestly, I can’t imagine the daily distribution needs.) A few days later there will be clouds of dung beetles. Deer and wild turkey and quail will graze with and behind the herd, not to mention the swallows swooping in above the herd as it grazes quietly along.

But surely we can do more with that ground. Cows appreciate shade on hot days. What if we planted rows of trees on contour? Miles and miles of diverse tree stands. Canopy layers of oak, hickory, chestnut or walnut. Lower layers of apple and cherry and filberts all on neat rows slowing the downhill flow of rainwater. Even lower layers of gooseberry and raspberry and strawberry. Black locust mixed in for nitrogen and wood products. All 12 million people in Illinois could have 50 pounds of cracked walnuts, 100 pounds of chestnuts, boxes and boxes of apples and cherries and strawberries. Of course, nobody wants all that food so we’ll have to hire people to harvest the abundance and build huge processing facilities to make brownies and High Fructose Chestnut Syrup and hard cider and applesauce and apple pie and caramel apples. Not to mention the massive squirrel and rabbit harvest…also enjoyed by the numerous birds of prey.

We would need something like one hired hand per thousand head of livestock so we’ll have at least 55,000 employees (probably on horseback) helping to manage the herd, culling old, open or injured animals, castrating young bulls and rams, keeping the mob grouped and moving. This does not count the teams that move ahead of the herds to build fence. (Not the kind of fence that subdivides the pasture for daily moves, the kind of fence that keeps the cows out of town…the houses from being smashed…and the cars from being trampled (we hope) by FIFTY-FIVE MILLION ANIMALS.) Probably another employee per thousand layers. Nor does this count their families that will accompany them on the migration amounting to a population larger than the city of Springfield. We’ll need many, many more people to help us transport, slaughter and distribute the meat. Thousands more to handle the abundance of nuts, fruit…just the raw materials. More to take those raw materials and produce finished products ranging from rawhide bones for pets to dining room tables to gooseberry pies. Think of the regulators required to keep us all safe! Think of the lawyers we’ll hire to keep us safe from the regulators!

And this is just the beginning. Remember, we set aside 15 million acres for humans. That leaves room for zucchini and tomatoes and flocks of chickens at home. Different strains of chickens…regional breeds. Maybe goats. Certainly pigs…everybody loves bacon. Pork may become that treasured annual delicacy bringing family together for harvest and celebration. Maybe one farmer in 20 farrows, allowing many others to keep a pig or two at home to make good use of uncollected tree nuts and garden waste. Maybe even home dairy. Heck, maybe small raw milk dairies to supply milk and cheese for neighbors…nevermind. Illinois doesn’t like raw milk. Sigh. Woodworking shops, welding and repair, bakeries, septic tank clean out… Heck, we’ll keep everybody so busy managing our abundance they won’t have time to write silly legislation to “fix” the world’s problems…let alone write starry-eyed, idealistic blog posts.

Do you know the difference between “riches” and “wealth”? What if I suggested rich people have an abundance of money and wealthy people have an abundance of time? How’s that sitting with you? (I’m thinking about this as I read P.G. Wodehouse.) Anyway, look man. When the herd is in your neighborhood, help us out. I’ll cut out a few head for your butchers and we’ll be back in a few months. When the herd is away, harvest the abundance of the forest. Bake a pecan pie sweetened with honey and pour a few mugs of hard cider. Sell the surplus production from your land then go fishing. No big whoop. Either you can lease me your grazing rights or you can lease space from me to plant your trees. Nobody is giving anybody anything. We all work hard. We all hold our heads up. We all become more wealthy (free time) and the money and resources we generate stay right here. You can buy that cool new techno-gadget if you want. I’m going to park my tookus under a tree near the herd and do some reading. Lamb for dinner. Again.

And what if we expanded the herd further? What if we worked with neighboring states to put together a larger migratory herd (probably herds)? Cottage industries springing up to help meet the needs of the families that stay with the herd year-round. There were somewhere north of 60 million bison ranging the plains 400 years ago….so…why not? Tens of thousands of people staying with the herd or working regionally with the herd as it passes through their area. Why not?

I’ll tell you why not. The EPA would shut it down.

Click image for source.

My goodness! How did the waterways survive before we shot all those horrible buffalo? What we need are more tractors! We need to rip the soil so the rain will wash it away. Put that stuff in the Gulf of Mexico where it belongs! By golly, God gave us a crater to fill and we’re gonna fill it! While we are at it, let’s poison the drinking water with weed sprays and bug sprays and anti-fungal sprays. Apparently cow poop in a stream and voluntary consumption of raw dairy will bring about the end of the world and don’t even mention the dead buffalo Lewis and Clark found in the Missouri River. Let’s sterilize the whole state right down to the bedrock. And it’s important that we tile the state to drain the rain away as quickly as possible too…in large part because atrazine in the ground water has become a bit of a problem. By golly, we have to feed the world and corn is the only way to do it.

So we’ll just continue on our current course. Eating corn flakes and puffed corn curls covered in corn starch cheese and drinking fizzy corn drinks and feeding corn to diarrhea-covered cattle in EPA-approved feedlots. Wasting our unhappy lives in cubicle-filled bureaucracies, out of touch with the natural world, never facing the reality of death…believing pharmacies and money can cure a lifetime of poor health choices…never accepting that the hamburger came from a beautiful living animal…and that it is OK to have mixed feelings about eating animals…that this is a discussion we can have. It’s OK to revere life…and take it carefully. Respectfully. To ensure our animals live each day with purpose. To ensure our people live each day with purpose. To save our soil for future generations. Nope. We can’t have that.