My farm didn’t come with a manual. No formula. Nothing set in stone. No function you plug values into. “You take X cows, you take Y acres and you allow Z time and voila, wealth, drought-resistance and ecological diversity.” No 8-minute YouTube video that will teach you the simple secrets of livestock management on this farm. Just soundbites here and there. Things you glean from years of reading books, listening to presentations and, ultimately, doing it all wrong. I just have to do the best I can and make mistakes along the way. As an added bonus, I brag about my mistakes on the internet for all to read!

Allow me to describe the farm as I bought it then we’ll take a look at where I hope it’s going…eventually.

We moved to the farm house because we had to. We had a beautiful home in suburbia with really nice neighbors. We felt safe. We were obviously weird owning one car, mowing the grass with a reel mower, home schooling our kids and cooking our own food but still, we were able to find meaningful relationships and fun. I installed hardwood floors, updated the wiring, built bookshelves galore, cabinets and a window seat. We made the house a home. But somehow it wasn’t our home…just a place we were visiting. We began looking for a few acres. We thought we would go ahead and list our house and by the time it sold we’d find a new place to live. Well, word of mouth travels fast and before we got the house listed we sold for our asking price. We had a month to get out and no place to go.

“Well, Grandma’s house is empty.”

So we rented Grandma’s house, not intending to stay. It was just a place to put our stuff until we could move closer to town again. Just a couple of acres. That’s all we needed. We couldn’t find a couple of acres. Our business began to grow. We could no longer sustain our meat, egg and goat milk business on an acre (the yard). We had to grow. So we made arrangements with my grandma and my uncle to buy 60 acres of the farm…20 acres now, 40 later. Hoo boy. 20 acres. 20 acres of thorns. 20 acres that had been grazed almost continuously my entire life and, apparently, had pigs on it constantly before I was born. 20 eroded, weedy, nasty, thorny acres of hills and eroded creek bed far from our primary customer base with the promise of another 40 of the same. (Did I mention the buildings were (are) in worse condition than the pastures? How about the fences?)

OK. What’s the plan? On top of a decade spent reading, studying and getting some hands-on experience we spent the first few years on the farm allowing a tenant to graze the land while we cut brush. Dad mowed the pasture so we could sled. Then dad got his tractor tires repaired from thorn damage. We added chickens and goats in rotation around the tenant’s cattle. Where the goats and chickens had been the grass grew best. The tenant’s cows spent most of their time on my 20 acres (not the other 40 acres they had access to) eating, tromping and manuring, though unmanaged. It was obvious that the pasture was improving, the grass density was increasing and the thorny things were being pushed back (though never defeated) by the goat grazing and the goat and chicken manure. There were fewer thorns in the sled trails every year.

That takes us to now. The tenant’s cows are mostly fenced out of our 20 (hungry calves still break in from time to time because we have standing grass in the winter and they don’t). Summer is coming to a close and we are 4 weeks from frost (though it’s over 100 degrees out today). Our cows are grazing tall pasture in tight, managed, planned rotation. The girls get fresh forage each day and tromp and manure the ground as they pass. We overseed where the cows and pigs have already been hoping to increase the diversity of grasses and forbs available in coming rotations…hoping to stretch grazing further into the year with increased plant diversity. 6-12 weeks later we graze the ground again meaning that I have at least 6-12 weeks of standing forage at all times. Over the winter we’ll graze in strips working to stretch our limited hay supply. Greg Judy says every inch of grass you can grow is a day you don’t have to feed hay. If the fall is mild grass could continue growing into December…even if slowly. Next year we’ll manage all 60 acres. The plan will stay the same.

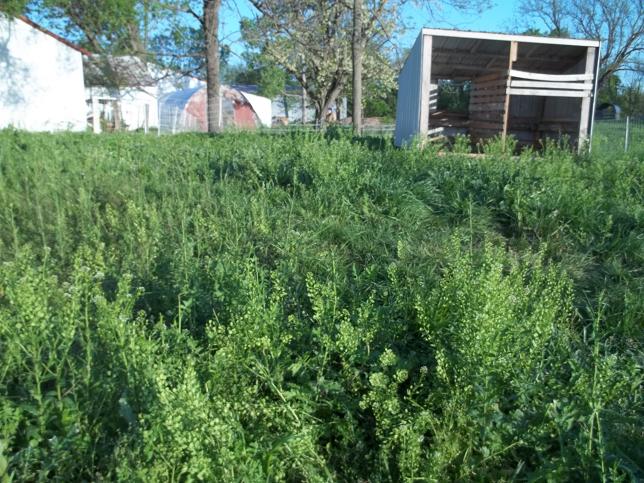

Will this work? The books say it should. But am I doing it right? I hope so. Heavy animal impact for short periods of time with long recovery periods in between grazings. The picture above was grazed this week. Am I setting my grass back long-term? Am I initializing a cycle of pasture improvement or continuing (or accelerating) pasture decline? I think I’m improving the pasture. There is definitely more grass out there than in years past and the cow paths are covered in grass. I’m not using a tractor, a plow, a disk, a harrow, a drill…just hooves, seed and a little hay. How many years will it be before I won’t need the hay anymore? All the books say I’ll start stretching later and later into the year without hay and then I won’t need any. Is that a function of land improvement or of increased management skill? Dunno.

I enjoy writing this, in part, to give our customers a window into our business. I also believe I’m making a contribution to a community that has inspired me…contributing to an open-source farming movement. Am I doing this right? I hope you can stick around for a few years to find out with me. I’m writing the manual for my farm. Hopefully my kids will be able to refer to it. Your farm manual will be very different. Are you writing a manual for your land or just playing it by ear?